COLUMN: Tales from the Gravel Ridge – Biodiversity and sustainability

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/07/2021 (1418 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

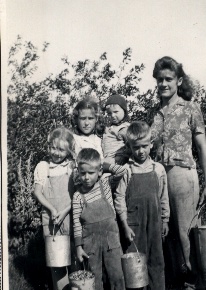

My experiences as a child growing up on a Manitoba farm during the 1940s, were diverse and wide-ranging, and for the most part wonderful. The fact that our farm was small, even by the standards of the day, did not by any means hinder my enjoyment of it. Nor was I especially aware of the limitations of such a small holding.

That farm, 20 acres initially, and in time expanded to 40 acres, was far from affording our family a lavish lifestyle, and did in fact require income from supplementary sources. In its own right however, it made available to us many benefits, some tangible, and many others intangible.

The tangible compensation provided by this relatively small piece of land, included the reality that much of our food supply could be produced on our farm. That in itself provided enormous advantages, especially the fact that many of our food items were close at hand, from fresh milk and eggs, to produce grown in our own gardens. During the summer that meant that we need merely go to the garden and bring in lettuce, onion greens, peas and beans, to name but a few. It was a task that even a child could readily achieve. Nutrition, in many respects, was close at hand, including, snacking on wild fruit growing entirely without cultivation in the woodlands of our farm.

A wide variety of plant life, which in turn was also habitat for wildlife and enormous varieties of insects could be found on our small Rosengard acreage. I think we took such biodiversity for granted. We collectively are beginning to recognize that such a cavalier disregard of the bounty of nature is a grave error on our part, one which cannot be easily reversed. If we think we’ll be just fine with the loss of biodiversity, I fear we are in for a rude awakening.

Memories of wild fruit on our farm included the gooseberry shrubs in our bush. Those memories take me back to the path taken by the cows as they went out to pasture. This path went directly through the woods, and was flanked by trees, mainly poplars, shrubs of numerous types, as well as a host of plants and grasses, and countless varieties of wildflowers. It seems to me that this trail was on somewhat low-lying land, and had its own micro-climate. Somehow this area seemed to favour the columbine, which always struck me as a very pretty flower, with its delicate red and yellow petals, drooping downward from a long stock.

The physical and material benefits of that small subsistence farm contributed substantially to the health and survival of our family during the years that we lived in Rosengard. I have no doubt that this was so for our entire community.

My parents had experienced numerous setbacks in life in war-torn Ukraine, and later in Canada during the Depression, which had little to do with their own choices. However, they had learned to take life in stride. This meant that they did not dwell on what might have been, or on what could not be changed. My parents were not given to complaining, or blaming themselves, or the rest of the world for what transpired in their lives. I was fortunate indeed to grow up in such a nurturing environment where children were expected to be responsible in their own role, but also allowed to be unfettered by events and concerns over which they had no control or for that matter, understanding.

This wonderful place was home to me for the first two decades of my life. It has taken me a long time to recognize and acknowledge the intrinsic value of some of the less readily discernible rewards it offered. Now, however, I comprehend more fully that those early childhood experiences in the context of my family and my community communicated to me the beauty and the sacredness of that place, even though I did not identify them so specifically at the time.