COLUMN: Carillon Flashback January 9, 1974 – Early Steinbach life revolved around Friesen Machine shop

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/04/2023 (969 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

From the modest appearance of Steinbach’s Friesen Machine Works, it is difficult to imagine that its founders were inventors, whose mechanical feats included the first straw blowers on the prairies and a 60-ton dragline, which worked on the aqueduct supplying Winnipeg with fresh drinking water from Shoal Lake.

In fact, this small machine shop was the most important business in the community for decades and more than any other, was responsible for the advanced mechanical technology available to the early Mennonite settlers in the Steinbach area.

It was located just a few yards south of its present location and its founders, K.R. and P.R. Friesen, were sons of Steinbach’s earliest mechanical wizard, A.S. Friesen, who brought the first steam engine to Steinbach. The Friesen Machine Shop was the centre of all mechanical work in the area, from simple wagon wheel repairs to complete steam boiler rebuilding.

Nearly every piece of machinery used in the district at one time or another passed through Friesen Machine Shop, and countless other pieces of equipment were built on the spot from raw metal, since manufactured goods didn’t become readily available until the 1930’s.

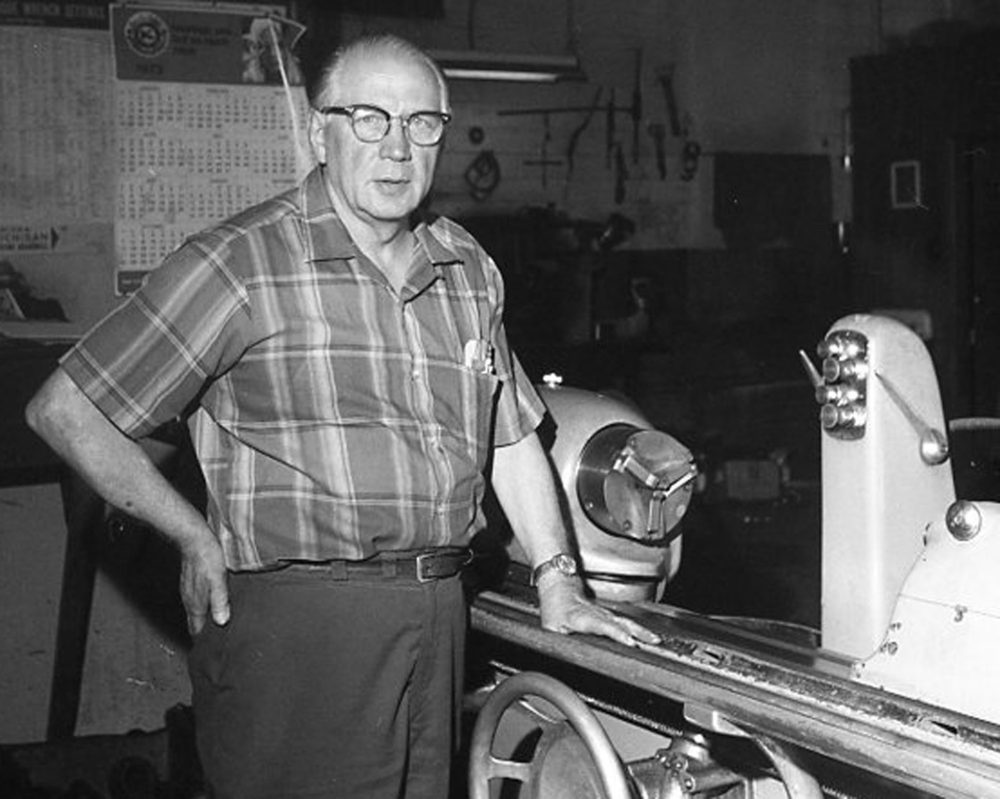

The original shop is gone, of course, and the current building was erected in 1938, and is the third since 1892, but the business is still owned and operated by the founders’ descendants. Barney Friesen, son of co-founder K.R. Friesen and grandson of A.S. Friesen, has saved a few pioneer shop tools, stamped with his father’s initials, to substantiate claims that his is indeed the oldest business in town.

Machine shop practises, admittedly, have come a long way from even 40 to 50 years ago, when cutting torches, arc welders and electric drills and grinders were unheard of, and all metal work had to be laboriously done with chisels, riveters and hand drills.

But, as Friesen points out, nothing can replace the natural mechanical ingenuity and inventiveness that the shop is known for, and hardly a day goes by that Friesen’s is not asked to build or modify a tool or piece of equipment to a customer’s demands.

The most significant change over the years was effected by advent of the gasoline engine, which during the 1920’s brought the automobile to dozens of local residents, and opened a whole new chapter of business development in Steinbach.

For the machine shop, cars meant engine repairs, instead of steam boiler rebuilding, and it wasn’t long before Friesen’s became known all over the Southeast as engine rebuilders of superb quality.

As engines, both gas and later diesel, became more sophisticated, so did the machinery and tools in the shop. Lathes became more automatic, power grinders replaced hand grinding and the incredible maze of overhead pulleys and belts, from which most tools were driven, was phased out as modern tools came equipped with their own compact electric motors.

The attic at Friesen Machine still holds a veritable treasure of tools, and if your 1934 Chevy needs new rings, there’s a brand new set of those up there as well, along with numerous mechanical devices, abandoned by the invention of the cutting torch in the 1930’s.

The cutting torch, Friesen says, reduced hours of tedious chiselling to minutes and represented a major advance at the time.

John D. Penner’s idea of converting steel tractor wheels to rubber tires, another local success story by itself, had a spin-off effect for the machine shop, which did much of the machining on wheels over which the new rubber tires were fitted.

Yet despite the dozens of specialty jobs the shop performs every week, the bulk of the work is still in engine rebuilding and re-machining of engine blocks, crankshafts, and other cast iron components.

And there has never been a decline in business over the years, as garages and other service outlets stock an ever increasing number of parts, Friesen points out that 20 years ago three people did everything in the shop and now it takes a total of eight, including two of his younger sons.